Superhumans Among Us: #Fastest40

FAYETTEVILLE, Ark. — How many steps did you take today?

Guidelines on health and exercise from the American Heart Association and other organizations recommend people take 10,000 steps or more per day, which is the equivalent of walking about five miles.

The increase in popularity of pedometers and fitness trackers like the various FitBit and Jawbone models that measure steps, heart rate, calories burned, and quality of sleep reflect a desire by many Americans to be more fit and lead healthier lives. According to a 2004 study of 200 men and women, men averaged 7,192 steps per day while women averaged 5,210 steps.

So how does 10,000 steps relate to The Fastest 40 Minutes In Basketball?

It doesn’t.

Steps as a metric of calculating movement and performance is largely obsolete in basketball where movement is a given constant.

Finding out that a player took 40,000 steps during practice isn’t a helpful metric and doesn’t provide coaches and strength and conditioning staff additional useful data, for example, how fast each player is moving and how much effort he is expending for a given amount of athletic performance.

Enter the Zephyr BioHarness.

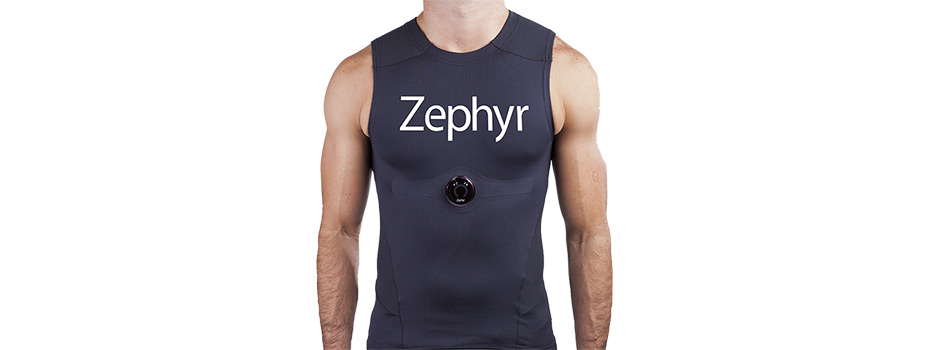

The Zephyr is a small, poker chip-sized puck that’s placed on a circular receptacle in the middle of a tight, form-fitting BioHarness Compression Shirt.

The Zephyr measures two sets of data points: Internal and external loads. The internal load stats include heart rate, respiration, and core temperature, while external loads measured include peak acceleration, activity level, and forward, backward and lateral (side-to-side) movement.

Ideally, Razorback coaches want to see low internal and high external loads. Think about it in terms of performance; you want to get the most return from running and jumping up-and-down on a basketball court while spending the least amount of energy and effort.

The internal and external loads measured by the Zephyr are then combined by the accompanying software and algorithms to generate a “training load” number; the higher the training load number, the better. It’s similar to the OVR figure in basketball video games like NBA 2K16.

We decided to track junior forward Moses Kingsley’s Zephyr stats and compare them to a non-athlete’s performance on workouts and drills similar to what the Razorbacks go through in practice. Kingsley was chosen because he consistently generated the lowest internal loads and the highest external loads on the team. As the non-athlete, I got to experience what The Fastest 40 is really about, while providing a base “training load” number to give context to Kingsley’s statistics.

So according to the charts below, I basically didn’t last too long. My #Fastest40 experience lasted only about 20 minutes before I had to stop for self-preservation. Razorback basketball players’ heart rates would routinely reach the 200-240 beats per minute (bpm) range during live action, and would fall to about 170-180 bpm during brief rests or instructional sessions. (If it’s not crystal clear already, Kingsley is the blue line on the graph, and I’m the black line.)

While I was able to get my heart rate up to 200 bpm, I just couldn’t match Kingsley’s level of physical intensity. If you had to compare apples-to-apples, this would be like comparing a mule cart next to a Ferrari.

This graph shows how much production Kingsley and I got from our physical exertion. While Kingsley’s rate of return got better over time, I barely broke even and I had to spend more and more energy to maintain my current output.

These graphs are a testament to the Fastest 40 philosophy head coach Mike Anderson instills into his players. When Razorbacks step on the court, they’re ready to outwork and outhustle you for 40 minutes and they’ll get stronger throughout the game as they work on whittling your energy reserves down to zero.

In 13 practice sessions measured by the Zephyr BioHarness, Kingsley averaged a training load score of 370.1. In comparison, my 20-minute Fastest 40 experience score was a paltry 16.8.

You’re a beast, Kingsley.

An additional benefit of gathering and examining live biometric data from players is being able to see where training staff can help players avoid injury during practice and games, and build up areas of their physical development in order to further their on-court performance. So along with the Zephyr BioHarness, Razorbacks Strength and Conditioning uses the Sparta Sports Science Force Plate.

The force plate was used by the Atlanta Falcons to measure Jadeveon Clowney’s athletic capabilities ahead of the 2014 NFL Draft, and now that same tool is being used to help our players improve their game and prevent injuries.

Basically, you stand on the middle of a plate fitted with sensors that track three metrics: Load, explode and drive.

“Load” is a person’s ability to produce force into the ground before the jump using your quadriceps; “explode” is the transition of the jump when you transfer load force back up using your core muscles; and “drive” is how you extend from the ground using your posterior muscles, hamstrings and glutes to produce jump height.

After waiting for the computer to get set, you’ll hear an audible “beep,” which is your signal to jump as high as you can with your arms raised in the air, and then land in the same exact spot. The system has a hair trigger; if you jump or move prematurely, the system will buzz and you have to start all over.

Just like the Zephyr, the Sparta Force Plate generates a final number based on the load, explode, and drive data inputs and it can tell trainers what sort of workouts to do with the player to improve their stats. The applications for this is obvious: Along with forward, backward and lateral movement, basketball requires players to jump and leap constantly throughout practices and games, and proper form must be taught and reinforced in order to prevent injury and drive improvement.

At a recent strength and conditioning session, Kingsley broke his personal best effort on the Force Place during his final attempt, scoring a 61.

To put Kingsley’s score of 61 in perspective, my best score out of six attempts was a 35. The system said I lacked sufficient drive, meaning I have underdeveloped hamstrings and glutes to allow me to jump really high.

I also wore my FitBit Charge HR during this whole experience. In case you’re wondering, 20 minutes of my #Fastest40 experience amounted to 5,051 steps, or about half of what’s considered the target amount for good health.

Overall, the Razorbacks’ use of sports science to further enhance the #Fastest40 philosophy means obtaining and using data to make better decisions. As effort in practice is quantified into easily digested numbers, coaches and training staff can make better game day decisions regarding player development and prevention of injury.

Combined with the world-class facilities at the University of Arkansas, Razorback student-athletes are at the forefront of pushing the sports competition envelope even further this season and beyond.